Chapter 3 Test Fairness

3.1 Introduction

Smarter Balanced has designed the assessment system to provide all eligible students with a fair test and equitable opportunity to participate in the assessment. Ensuring test fairness is a fundamental part of validity, starting with test design. It is an important feature built into each step of the test development process, such as item writing, test administration, and scoring. The 2014 Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (Standards; AERA, APA, & NCME, 2014, p. 49) state, “The term fairness has no single technical meaning, and is used in many ways in public discourse.” It also suggests that fairness to all individuals in the intended population is an overriding and fundamental validity concern. As indicated in the Standards (2014), “The central idea of fairness in testing is to identify and remove construct-irrelevant barriers to maximal performance for any examinee” (p. 63).

The Smarter Balanced system is designed to provide a valid, reliable, and fair measure of student achievement based on the state standards. The validity and fairness of student achievement measures are influenced by a multitude of factors; central among them are:

- a clear definition of the construct—the knowledge, skills, and abilities—intended to be measured;

- the development of items and tasks that are explicitly designed to assess the construct that is the target of measurement;

- the delivery of items and tasks that enable students to demonstrate their achievement on the construct; and

- the capturing and scoring of responses to those items and tasks.

Smarter Balanced uses several processes to address reliability, validity, and fairness. The fairness construct is defined in the state standards. The state standards are a set of high-quality academic standards in English language arts/literacy (ELA/literacy) and mathematics that outline what a student should know and be able to do at the end of each grade. The standards were created to ensure that all students graduate from high school with the skills and knowledge necessary for post-secondary success. The state standards were developed during a state-led effort launched in 2009 by state leaders. These leaders included governors and state commissioners of education from 48 states, two territories, and the District of Columbia, through their membership in the National Governors Association Center for Best Practices (NGA Center) and the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO).

The state standards have been adopted by all members of the Smarter Balanced Consortium. The Smarter Balanced content specifications (Smarter Balanced, 2017b, 2017d) define the knowledge, skills, and abilities to be assessed and their relationship to the state standards. In doing so, these documents describe the major constructs—identified as “claims”—within ELA/literacy and mathematics for which evidence of student achievement is gathered and that form the basis for reporting student performance.

Each claim in the Smarter Balanced content specifications is accompanied by a set of assessment targets that provide more detail about the range of content and depth of knowledge levels. The targets serve as the building blocks of test blueprints. Much of the evidence presented in this chapter pertains to fairness to students during the testing process and to design elements and procedures that serve to minimize measurement bias (i.e., Differential Item Functioning, or DIF). Fairness in item and test design processes and the design of accessibility resources (i.e., universal tools, designated supports, and accommodations) in content development are also addressed.

3.2 Definitions for Validity, Bias, Sensitivity, and Fairness

Some key concepts for the ensuing discussion concern validity, bias, sensitivity, and fairness and are described as follows.

3.2.1 Validity

Validity is the extent to which the inferences and actions based on test scores are appropriate and backed by evidence (Messick, 1989). It constitutes the central notion underlying the development, administration, and scoring of a test, as well as the uses and interpretations of test scores. Validation is the process of accumulating evidence to support each proposed score interpretation or use. Evidence in support of validity is extensively discussed in Chapter 1.

3.2.2 Bias

According to the Standards (2014), bias is “construct underrepresentation or construct-irrelevant components of tests scores that differentially affect the performance of different groups of test takers and consequently affect the reliability/precision and validity of interpretations and uses of test scores” (p. 216).

3.2.3 Sensitivity

“Sensitivity” refers to an awareness of the need to avoid explicit bias in assessment. In common usage, reviews of tests for bias and sensitivity help ensure that test items and stimuli are fair for various groups of test takers (AERA, APA, & NCME, 2014, p. 64).

3.2.4 Fairness

The goal of fairness in assessment is to ensure that test materials are as free as possible from unnecessary barriers to the success of diverse groups of students. Smarter Balanced developed the Bias and Sensitivity Guidelines (Smarter Balanced, 2022a) to help ensure that the assessments are fair for all groups of test takers, despite differences in characteristics that include, but are not limited to, disability status, ethnic group, gender, regional background, native language, race, religion, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic status. Unnecessary barriers can be reduced by:

- measuring only knowledge or skills that are relevant to the intended construct;

- not angering, offending, upsetting, or otherwise distracting test takers; and

- treating all groups of people with appropriate respect in test materials.

These rules help ensure that the test content is fair for test takers and acceptable to the many decision makers and constituent groups within Smarter Balanced member organizations. The more typical view is that bias and sensitivity guidelines apply primarily to the review of test items. However, fairness must be considered in all phases of test development and use.

3.3 Bias and Sensitivity Guidelines

Smarter Balanced strongly relied on the Bias and Sensitivity Guidelines in the development of the Smarter Balanced assessments, particularly in item writing and review. Items must comply with these guidelines in order to be included in the Smarter Balanced assessments. Use of the guidelines will help the Smarter Balanced assessments comply with Chapter 3, Standard 3.2 of the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing. Standard 3.2 states that “test developers are responsible for developing tests that measure the intended construct and for minimizing the potential for tests being affected by construct-irrelevant characteristics such as linguistic, communicative, cognitive, cultural, physical or other characteristics” (AERA, APA, & NCME, 2014, p. 64).

Smarter Balanced assessments were developed using the principles of evidence-centered design (ECD). ECD requires a chain of evidence-based reasoning that links test performance to the claims made about test takers. Fair assessments are essential to the implementation of ECD. If test items are not fair, then the evidence they provide means different things for different groups of students. Under those circumstances, the claims cannot be equally supported for all test takers, which is a threat to validity. As part of the validation process, all items are reviewed for bias and sensitivity using the Bias and Sensitivity Guidelines (Smarter Balanced, 2022a) prior to being presented to students. This helps ensure that item responses reflect only knowledge of the intended content domain, are free of offensive or distracting material, and portray all groups in a respectful manner. When the guidelines are followed, item responses provide evidence that supports assessment claims.

3.3.1 Item Development

Smarter Balanced has established item development practices that maximize access for all students, including English Learners (ELs), students with disabilities, and ELs with disabilities, but not limited to those groups. The Smarter Balanced Item and Task Specifications Bibliography (Smarter Balanced, 2016d), the Smarter Balanced Accessibility and Accommodations Framework (Smarter Balanced, 2016b), the Smarter Balanced Bias and Sensitivity Guidelines, and the Usability, Accessibility, and Accommodations, Guidelines (Smarter Balanced, 2023c), are used to guide the development of items and tasks to ensure that they accurately measure the targeted constructs. Recognizing the diverse characteristics and needs of students who participate in the Smarter Balanced assessments, the states worked together through the Smarter Balanced Test Administration and Student Access Work Group to incorporate research and practical lessons learned through universal design, accessibility tools, and accommodations (Thompson et al., 2002).

A fundamental goal is to design an assessment that is accessible for all students, regardless of English language proficiency, disability, or other individual circumstances. The intent is to ensure that the following steps were achieved for Smarter Balanced.

- Design and develop items and tasks to ensure that all students have access to the items and tasks. In addition, deliver items, tasks, and the collection of student responses in a way that maximizes validity for each student.

- Adopt the conceptual model embodied in the Accessibility and Accommodations Framework (Smarter Balanced, 2016b) that describes accessibility resources of digitally delivered items/tasks and acknowledges the need for some adult-monitored accommodations. The model also characterizes accessibility resources as a continuum ranging from those available to all students, those that are implemented under adult supervision only, and those for students with a documented need.

- Implement the use of an individualized and systematic needs profile for students, or Individual Student Assessment Accessibility Profile (ISAAP), that promotes the provision of appropriate access and tools for each student. Smarter Balanced created an ISAAP process, which helps education teams systematically select the most appropriate accessibility resources for each student, and the ISAAP tool, which helps teams note the accessibility resources chosen.

Prior to any item development and item review, Smarter Balanced staff trains item writers and reviewers on the General Accessibility Guidelines (Smarter Balanced, 2012a) and Bias and Sensitivity Guidelines (Smarter Balanced, 2022a). As part of item review, individuals with expertise in accessibility, bias, and sensitivity review each item and compare it against a checklist for accessibility and bias and sensitivity. Items must pass each criterion on both checklists to be eligible for field testing. By relying on universal design to develop the items and requiring that individuals with expertise in bias, sensitivity, and accessibility review the items throughout the iterative process of development, Smarter Balanced ensures that the items are appropriate for a wide range of students.

3.3.2 Guidelines for General Accessibility

In addition to implementing the principles of universal design during item development, Smarter Balanced meets the needs of ELs by addressing language aspects during development, as described in the Guidelines for Accessibility for English Language Learners (Smarter Balanced, 2012b). ELs have not yet acquired proficiency in English. The use of language that is not fully accessible can be regarded as a source of invalidity that affects the resulting test score interpretations by introducing construct-irrelevant variance. Although there are many validity issues related to the assessment of ELs, the main threat to validity when assessing content knowledge stems from language factors that are not relevant to the construct of interest. The goal of these EL guidelines was to minimize factors that are thought to contribute to such construct-irrelevant variance. Adherence to these guidelines helped ensure that, to the greatest extent possible, the Smarter Balanced assessments administered to ELs measure the intended targets. The EL guidelines were intended primarily to inform Smarter Balanced assessment developers or other educational practitioners, including content specialists and testing coordinators.

In educational assessments, there is an important distinction between content-related language that is the target of instruction versus language that is not content related. For example, the use of words with specific technical meaning, such as “slope” when used in algebra or “population” when used in biology, should be used to assess content knowledge for all students. In contrast, greater caution should be exercised when including words that are not directly related to the domain. ELs may have had cultural and social experiences that differ from those of other students. Caution should be exercised in assuming that ELs have the same degree of familiarity with concepts or objects occurring in situational contexts. The recommendation was to use contexts or objects based on classroom or school experiences, rather than ones that are based outside of school. For example, in constructing mathematics items, it is preferable to use common school objects, such as books and pencils, rather than objects in the home, such as kitchen appliances, to reduce the potential for construct-irrelevant variance associated with a test item. When the construct of interest includes a language component, the decisions regarding the proper use of language become more nuanced. If the construct assessed is the ability to explain a mathematical concept, then the decisions depend on how the construct is defined. If the construct includes the use of specific language skills, such as the ability to explain a concept in an innovative context, then it is appropriate to assess these skills. In ELA/literacy, there is greater uncertainty as to item development approaches that faithfully reflect the construct while avoiding language inaccessible for ELs.

The decisions of what best constitutes an item can rely on the content standards, the definition of the construct, and the interpretation of the claims and assessment targets. For example, if the skill to be assessed involves interpreting meanings in a literary text, then the use of original source materials is acceptable. However, the test item itself—as distinct from the passage or stimulus—should be written so that the task presented to a student is clearly defined using accessible language. Since ELs taking Smarter Balanced content assessments likely have a range of English proficiency skills, it is also important to consider the accessibility needs across the entire spectrum of proficiency. Since ELs, by definition, have not attained complete proficiency in English, the major consideration in developing items is ensuring that the language used is as accessible as possible. The use of accessible language does not guarantee that construct-irrelevant variance will be eliminated, but it is the best strategy for helping ensure valid scores for ELs and for other students as well.

Using clear and accessible language is a key strategy that minimizes construct-irrelevant variance in items. Language that is part of the construct being measured should not be simplified. For non-content-specific text, the language of presentation should be as clear and simple as possible. The following guidelines for the use of accessible language were proposed as guidance in the development of test items. This guidance is intended to work in concert with other principles of good item construction. From the ELL Guidelines (Smarter Balanced, 2012b), some general principles for the use of accessible language were proposed as follows.

Design test directions to maximize clarity and minimize the potential for confusion.

Use vocabulary widely accessible to all students, and avoid unfamiliar vocabulary not directly related to the construct (August et al., 2005; Bailey et al., 2007).

Avoid the use of syntax or vocabulary that is above the test’s target grade level (Borgioli, 2008). The test item should be written at a vocabulary level no higher than the target grade level, and preferably at a slightly lower grade level, to ensure that all students understand the task presented (Young, 2008).

Keep sentence structures as simple as possible while expressing the intended meaning. In general, ELs find a series of simpler, shorter sentences to be more accessible than longer, more complex sentences (Pitoniak et al., 2009).

Consider the impact of cognates (words with a common etymological origin) and false cognates (word pairs or phrases that appear to have the same meaning in two or more languages, but do not) when developing items. Spanish and English share many cognates, and because the large majority of ELs speak Spanish as their first language (nationally, more than 75%), the presence of cognates can inadvertently confuse students and alter the skills being assessed by an item. Examples of false cognates include: billion (the correct Spanish translation is mil millones; not billón, which means trillion); deception (engaño; not decepción, which means disappointment); large (grande; not largo, which means long); library (biblioteca; not librería, which means bookstore).

Do not use cultural references or idiomatic expressions (such as “being on the ball”) that are not equally familiar to all students (Bernhardt, 2005).

Avoid sentence structures that may be confusing or difficult to follow, such as the use of passive voice or sentences with multiple clauses (Abedi & Lord, 2001; Forster & Olbrei, 1973; Schachter, 1983).

Do not use syntax that may be confusing or ambiguous, such as using negation or double negatives in constructing test items (Abedi, 2006; Cummins et al., 1988).

Minimize the use of low-frequency, long, or morphologically complex words and long sentences (Abedi et al., 1995; Abedi, 2006).

Teachers can use multiple semiotic representations to convey meaning to students in their classrooms. Assessment developers should also consider ways to create questions using multi-semiotic methods so that students can better understand what is being asked (Kopriva, 2010). This might include greater use of graphical, schematic, or other visual representations to supplement information provided in written form.

3.4 Test Delivery

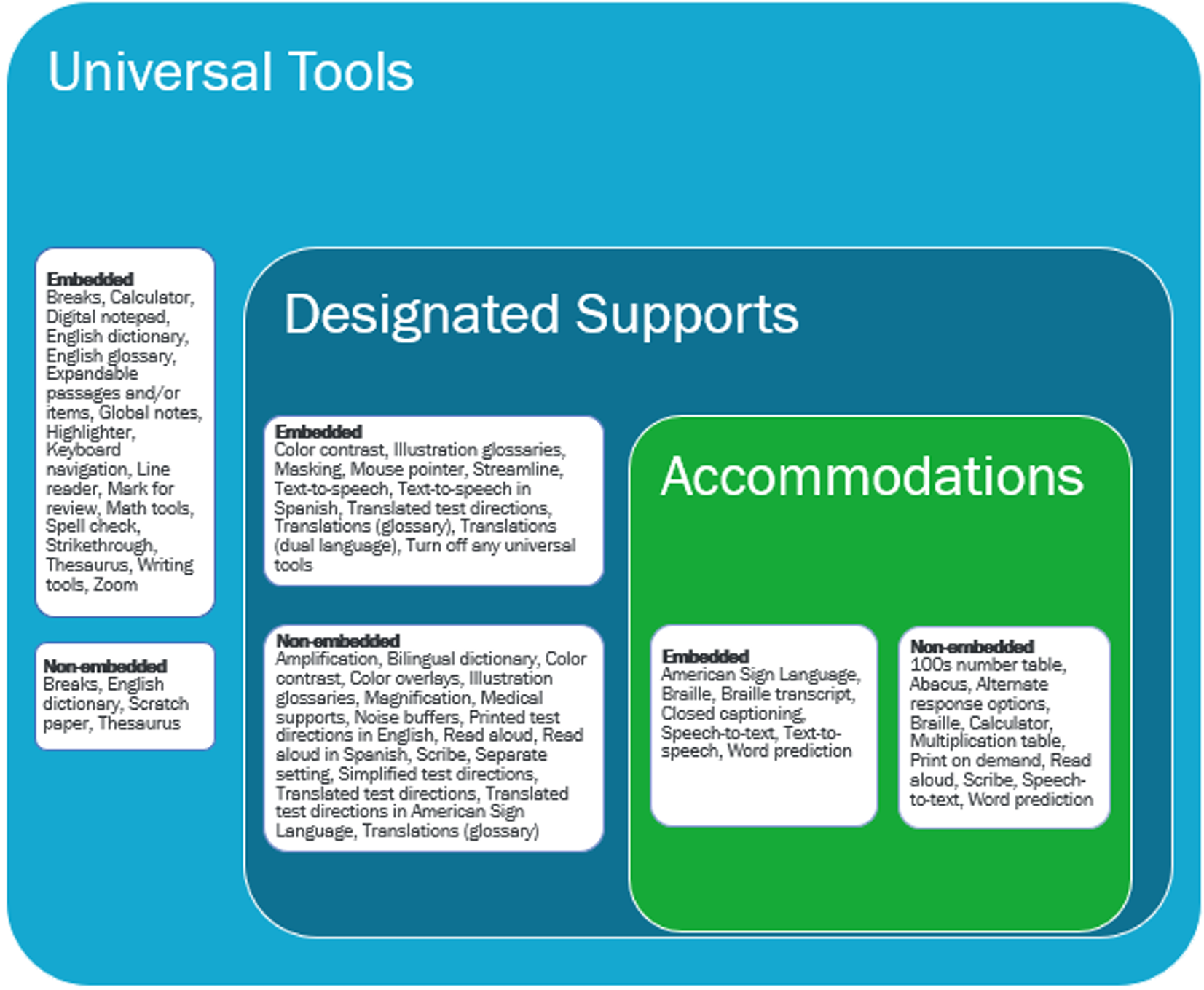

In addition to focusing on accessibility, bias, and sensitivity during item development, Smarter Balanced also maximizes accessibility through test delivery. Smarter Balanced works with members to maintain the original conceptual framework (Smarter Balanced, 2016b) that continues to serve as the basis underlying the usability, accessibility, and accommodations (Figure 3.1). This figure portrays several aspects of the Smarter Balanced assessment resources—universal tools (available for all students), designated supports (available when indicated by an adult or team), and accommodations (as documented in an Individualized Education Program (IEP) or 504 plan). It also displays the additive and sequentially inclusive nature of these three aspects.

Universal tools are available to all students, including those receiving designated supports and those receiving accommodations.

Designated supports are available only to students who have been identified as needing these resources (as well as those students for whom the need is documented as described in the following point).

Accommodations are available only to those students with documentation of the need through a formal plan (e.g., IEP, 504). Those students also may access designated supports and universal tools.

A universal tool or a designated support may also be an accommodation, depending on the content or grade. This approach is consistent with the emphasis that Smarter Balanced has placed on the validity of assessment results coupled with access. Universal tools, designated supports, and accommodations are all intended to yield valid scores. Use of universal tools, designated supports, and accommodations result in scores that count toward participation in statewide assessments. Also shown in Figure 3.1 are the universal tools, designated supports, and accommodations for each category of accessibility resources. There are both embedded and non-embedded versions of the universal tools, designated supports, or accommodations, depending on whether they are provided as digitally delivered components of the test administration or provided locally separate from the test delivery system.

Figure 3.1: Conceptual Model Underlying the Smarter Balanced Usability, Accessibility, and Accommodations Guidelines

3.5 Meeting the Needs of Traditionally Underrepresented Populations

Members decided to make accessibility resources available to all students based on need rather than eligibility status or other designation. This reflects a belief among Consortium states that unnecessarily restricting access to accessibility resources threatens the validity of the assessment results and places students under undue stress and frustration. Additionally, accommodations are available for students who qualify for them. The Consortium utilizes a needs-based approach to providing accessibility resources. A description as to how this benefits ELs, students with disabilities, and ELs with disabilities is presented here.

3.5.1 Students Who Are ELs

Students who are ELs have needs that are unique from students with disabilities, including language-related disabilities. The needs of ELs are not the result of a language-related disability, but instead are specific to the student’s current level of English language proficiency. The needs of students who are ELs are diverse and are influenced by the interaction of several factors, including their current level of English language proficiency, their prior exposure to academic content and language in their primary language, the languages to which they are exposed outside of school, the length of time they have participated in the U.S. education system, and the language(s) in which academic content is presented in the classroom. Given the unique background and needs of each student, the conceptual framework is designed to focus on students as individuals and to provide several accessibility resources that can be combined in a variety of ways. Some of these digital tools, such as using a highlighter to highlight key information, are available to all students, including ELs. Other tools, such as the audio presentation of items or glossary definitions in English, may also be assigned to any student, including ELs. Still, other tools, such as embedded glossaries that present translations of construct-irrelevant terms, are intended for those students whose prior language experiences would allow them to benefit from translations into another spoken language. Collectively, the conceptual framework for usability, accessibility, and accommodations embraces a variety of accessibility resources that have been designed to meet the needs of students at various stages in their English language development.

3.5.2 Students and English Learners with Disabilities

Federal law requires that students with disabilities who have a documented need receive accommodations that address those needs and that they participate in assessments. The intent of the law is to ensure that all students have appropriate access to instructional materials and are held to the same high standards. When students are assessed, the law ensures that students receive appropriate accommodations during testing so they can demonstrate what they know and can do, and so that their achievement is measured accurately.

The Accessibility and Accommodations Framework (Smarter Balanced, 2016b) addresses the needs of students with disabilities in three ways. First, it provides for the use of digital test items that are purposefully designed to contain multiple forms of the item, each developed to address a specific access need. By allowing the delivery of a given access form of an item to be tailored based on each student’s access need, the Framework fulfills the intent of federal accommodation legislation. Embedding universal accessibility digital tools, however, addresses only a portion of the access needs required by many students with disabilities. Second, by embedding accessibility resources in the digital test delivery system, additional access needs are met. This approach fulfills the intent of the law for many, but not all, students with disabilities by allowing the accessibility resources to be activated for students based on their needs. Third, by allowing for a wide variety of digital and locally provided accommodations (including physical arrangements), the Framework addresses a spectrum of accessibility resources appropriate for ELA/literacy and mathematics assessment. Collectively, the Framework adheres to federal regulations by allowing a combination of universal design principles, universal tools, designated supports, and accommodations to be embedded in a digital delivery system and through local administration assigned and provided based on individual student needs. Therefore, a student who is both an EL and a student with a disability benefits from the system because they may have access to resources from any of the three categories (universal tools, designated supports, accommodations) as necessary to create an assessment tailored to their individual need.

3.6 The Individual Student Assessment Accessibility Profile (ISAAP)

Typical practice frequently required schools and educators to document, a priori, the need for specific student accommodations and document the use of those accommodations after the assessment. For example, most programs require schools to document a student’s need for a large-print version of a test for delivery to the school. Following the test administration, the school documented (often by bubbling in information on an answer sheet) which of the accommodations, if any, a given student received; whether the student actually used the large-print form; and whether any other accommodations, such as extended time, were provided. Traditionally, many programs have focused only on students who have received accommodations and thus may consider an accommodation report as documenting accessibility needs. The documentation of need and use establishes a student’s accessibility needs for assessment.

For most students, universal digital tools are available by default in the Smarter Balanced test delivery system and need not be documented. These tools can be deactivated if they create an unnecessary distraction for the student. Other embedded accessibility resources that are available for any student needing them must be documented prior to assessment. The Smarter Balanced assessment system has established an Individual Student Assessment Accessibility Profile (ISAAP) to capture specific student accessibility needs. The ISAAP tool is designed to facilitate the selection of the universal tools, designated supports, and accommodations that match student access needs for the Smarter Balanced assessments, as supported by the Usability, Accessibility, and Accommodations Guidelines (Smarter Balanced, 2023c). The ISAAP tool3 should be used in conjunction with the Usability, Accessibility, and Accommodations Guidelines and state regulations and policies related to assessment accessibility as a part of the ISAAP process. For students requiring one or more accessibility resources, schools will be able to document this need prior to test administration. Furthermore, the ISAAP can include information about universal tools that may need to be eliminated for a given student. By documenting the need prior to test administration, a digital delivery system will be able to activate the specified options when the student logs in to an assessment. In this way, the profile permits school-level personnel to focus on each individual student, documenting the accessibility resources required for valid assessment of that student in a way that is efficient to manage.

The conceptual framework shown in Figure 3.1 provides a structure that assists in identifying which accessibility resources should be made available for each student. In addition, the conceptual framework is designed to differentiate between universal tools available to all students and accessibility resources that must be assigned before the administration of the assessment. Consistent with recommendations from Shafer Willner & Rivera (2011); Thurlow et al. (2011); Fedorchak (2012); and Russell (2011), Smarter Balanced is encouraging school-level personnel to use a team approach to make decisions concerning each student’s ISAAP. Gaining input from individuals with multiple perspectives, including the student, will likely result in appropriate decisions about the assignment of accessibility resources. Consistent with these recommendations, one should avoid selecting too many accessibility resources for a student. The use of too many unneeded accessibility resources can decrease student performance.

The team approach encouraged by Smarter Balanced does not require the formation of a new decision-making team. The structure of teams can vary widely depending on the background and needs of a student. A locally convened student support team can potentially create the ISAAP. For most students who do not require accessibility tools or accommodations, a teacher’s initial decision may be confirmed by a second person (potentially the student). In contrast, for a student who is an English learner and has been identified with one or more disabilities, the IEP team should include the English language development specialist who works with the student, along with other required IEP team members and the student, as appropriate. The composition of teams is not being defined by Smarter Balanced; it is under the control of each school and is subject to state and federal requirements.

3.7 Usability, Accessibility, and Accommodations Guidelines

Smarter Balanced developed the Usability, Accessibility, and Accommodations Guidelines (UAAG) (Smarter Balanced, 2023c) for its members to guide the selection and administration of universal tools, designated supports, and accommodations. All Interim Comprehensive Assessments (ICAs) and Interim Assessment Blocks (IABs) are fully accessible and offer all accessibility resources as appropriate by grade and content area, including American Sign Language (ASL), braille, and Spanish. It is intended for school-level personnel and decision-making teams, particularly Individualized Education Program (IEP) teams, as they prepare for and implement the Smarter Balanced summative and interim assessments. The UAAG provides information for classroom teachers, English development educators, special education teachers, and related services personnel in selecting and administering universal tools, designated supports, and accommodations for those students who need them. The UAAG is also intended for assessment staff and administrators who oversee the decisions that are made in instruction and assessment. It emphasizes an individualized approach to the implementation of assessment practices for those students who have diverse needs and participate in large-scale assessments. This document focuses on universal tools, designated supports, and accommodations for the Smarter Balanced summative and interim assessments in ELA/literacy and mathematics. At the same time, it supports important instructional decisions about accessibility for students. It recognizes the critical connection between accessibility in instruction and accessibility during assessment. The UAAG is also incorporated into the Smarter Balanced Test Administration Manual (Smarter Balanced, 2021b).

According to the UAAG (Smarter Balanced, 2023c), all eligible students (including students with disabilities, ELs, and ELs with disabilities) should participate in the assessments. In addition, the performance of all students who take the assessment is measured with the same criteria. Specifically, all students enrolled in grades 3-8 and high school are required to participate in the Smarter Balanced mathematics assessment, except students with the most significant cognitive disabilities who meet the criteria for the mathematics alternate assessment based on alternate achievement standards (approximately 1% or fewer of the student population).

All students enrolled in grades 3-8 and high school are required to participate in the Smarter Balanced ELA/literacy assessment except:

- students with the most significant cognitive disabilities who meet the criteria for the English language arts/literacy alternate assessment based on alternate achievement standards (approximately 1% or fewer of the student population), and

- ELs who are enrolled for the first year in a U.S. school. These students will participate in their state’s English language proficiency assessment.

Federal laws governing student participation in statewide assessments include the Elementary and Secondary Education Act ESEA (reauthorized as the Every Student Succeeds Act ESSA of 2015), the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004 IDEA, and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (reauthorized in 2008).

Since the Smarter Balanced assessment is based on the state standards, universal tools, designated supports, and accommodations, the Smarter Balanced assessment may be different from those that state programs utilized previously. For the summative assessments, state participants can only make available to students the universal tools, designated supports, and accommodations consistent with the Smarter Balanced UAAG. According to the UAAG (Smarter Balanced, 2023c), when the implementation or use of the universal tool, designated support, or accommodation is in conflict with a member state’s law, regulation, or policy, a state may elect not to make it available to students.

The Smarter Balanced universal tools, designated supports, and accommodations currently available for the Smarter Balanced assessments have been prescribed. The specific universal tools, designated supports, and accommodations approved by Smarter Balanced may undergo change if additional tools, supports, or accommodations are identified for the assessment based on state experience or research findings. The Consortium has established a standing committee, including members from the Consortium and staff, that reviews suggested additional universal tools, designated supports, and accommodations to determine if changes are warranted. Proposed changes to the list of universal tools, designated supports, and accommodations are brought to Consortium members for review, input, and vote for approval. Furthermore, states may issue temporary approvals (i.e., one summative assessment administration) for individual, unique student accommodations. It is expected that states will evaluate formal requests for unique accommodations and determine whether the request poses a threat to the measurement of the construct. Upon issuing temporary approval, the petitioning state can send documentation of the approval to the Consortium. The Consortium will consider all state-approved temporary accommodations as part of the annual Consortium accommodations review process. The Consortium will provide member states a list of the temporary accommodations issued by states that are not Consortium-approved accommodations.

3.8 Provision of Specialized Tests or Pools

Smarter Balanced provides a full item pool and a series of specialized item pools that allow students who are eligible to access the tests with a minimum of barriers. These accessibility resources are considered embedded accommodations or embedded designated supports. The specialized pools that were available in 2021-22 are shown in Table 3.1.

| Subject | Test Instrument |

|---|---|

| ELA/Literacy | ASL adaptive online (Listening only) |

| ELA/Literacy | Closed captioning adaptive online (Listening only) |

| ELA/Literacy | Braille adaptive online |

| ELA/Literacy | Braille paper pencil |

| Math | Translated glossaries adaptive online |

| Math | Illustrated glossaries adaptive online |

| Math | Dual language Spanish adaptive online |

| Math | ASL adaptive online |

| Math | Braille adaptive online |

| Math | Braille hybrid adaptive test (HAT) |

| Math | Spanish paper pencil |

| Math | Braille paper pencil |

| Math | Translated glossaries paper pencil |

| Math | Illustrated glossaries paper pencil |

Table 3.2 and Table 3.3 show, for each subject, the number of online items in the general and accommodated pools by test segment (CAT and performance task (PT)) and grade. Items in fixed forms, both online and paper/pencil, are not included in the counts shown in these tables.

| Segment | Grade | Online General | Online ASL | Online Braille |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAT | 3 | 889 | 55 | 250 |

| CAT | 4 | 848 | 58 | 229 |

| CAT | 5 | 822 | 44 | 235 |

| CAT | 6 | 803 | 54 | 239 |

| CAT | 7 | 739 | 46 | 191 |

| CAT | 8 | 758 | 51 | 241 |

| CAT | 11 | 2573 | 118 | 437 |

| PT | 3 | 50 | 0 | 10 |

| PT | 4 | 58 | 0 | 10 |

| PT | 5 | 58 | 0 | 10 |

| PT | 6 | 44 | 0 | 4 |

| PT | 7 | 60 | 0 | 16 |

| PT | 8 | 66 | 0 | 16 |

| PT | 11 | 58 | 0 | 14 |

| Segment | Grade | Online General | Online ASL | Online Braille | Online Translated Glossaries | Online Illustrated Glossaries | Online Spanish |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAT | 3 | 1236 | 404 | 401 | 407 | 292 | 479 |

| CAT | 4 | 1286 | 388 | 338 | 396 | 264 | 463 |

| CAT | 5 | 1255 | 426 | 371 | 414 | 253 | 475 |

| CAT | 6 | 1179 | 404 | 376 | 398 | 239 | 476 |

| CAT | 7 | 1142 | 384 | 353 | 357 | 171 | 456 |

| CAT | 8 | 973 | 362 | 299 | 325 | 164 | 387 |

| CAT | 11 | 2675 | 739 | 542 | 658 | 246 | 777 |

| PT | 3 | 95 | 41 | 41 | 40 | 18 | 56 |

| PT | 4 | 106 | 39 | 34 | 37 | 17 | 45 |

| PT | 5 | 123 | 45 | 45 | 33 | 24 | 55 |

| PT | 6 | 91 | 23 | 23 | 29 | 16 | 44 |

| PT | 7 | 86 | 26 | 26 | 21 | 17 | 26 |

| PT | 8 | 79 | 25 | 19 | 35 | 21 | 39 |

| PT | 11 | 71 | 22 | 17 | 37 | 21 | 38 |

Table 3.4 and Table 3.5 show the total score reliability and standard error of measurement (SEM) of the tests taken with the full blueprint by students requiring an accommodated pool of items. The statistics in these tables were derived as described in Chapter 2 for students in the general population. Results are only reported if there were at least 5 examinees in the grade and accomodation category. Braille was available in 2021-22 but is not reported here because this sample size reporting rule was not met for any grade.

The measurement precision of accommodated tests is in line with that of the general population, taking into consideration the overall performance of students taking the accommodated tests and the relationship between overall performance level and measurement error. Measurement error tends to be greater at higher and lower deciles of performance, compared to deciles near the median. To the extent that the average overall scale scores of students taking accommodated tests, shown in Table 3.4 and Table 3.5, fall into higher or lower deciles of performance (see tables in Section 5.4.3), one can expect the corresponding average SEMs in Table 3.4 and Table 3.5 to be larger than those for the general population. To the extent that average SEM associated with the accommodated tests tend to be larger for this reason, one can also expect reliability coefficients in Table 3.4 and Table 3.5 to be smaller than those for the general population (see total score reliabilities in Table 2.3 and Table 2.4). Any differences in reliability coefficients between general and accommodated populations must also take into account differences in variability of test scores. Even if the groups had the same average scale score and measurement error, the group having a lower standard deviation of scale scores would have a lower reliability coefficient.

Statistics concerned with test bias are reported for braille and Spanish tests in Chapter 2 and are based on simulation. Reliability and measurement error information for accommodated fixed forms, both paper/pencil and online, are the same for regular fixed forms, as reported in Table 2.9 and Table 2.10, since the accommodated and regular fixed forms use the same items.

| Type | Grade | N | Mean | SD | Rho | Avg.SEM | SEM.Q1 | SEM.Q2 | SEM.Q3 | SEM.Q4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Braille | 3 | 16 | 2417 | 81.3 | 0.859 | 30.4 | 31.2 | 32.8 | 27.0 | 32.0 |

| Braille | 4 | 23 | 2476 | 110.0 | 0.916 | 30.9 | 38.3 | 24.2 | 29.6 | 30.2 |

| Braille | 5 | 29 | 2437 | 129.6 | 0.884 | 39.2 | 62.3 | 36.1 | 27.9 | 31.7 |

| Braille | 6 | 31 | 2456 | 143.8 | 0.829 | 49.4 | 95.4 | 40.3 | 31.2 | 28.3 |

| Braille | 7 | 64 | 2486 | 105.3 | 0.841 | 39.9 | 56.4 | 37.1 | 35.2 | 30.5 |

| Braille | 8 | 47 | 2466 | 102.7 | 0.818 | 42.6 | 54.8 | 44.5 | 36.7 | 34.4 |

| Braille | HS | 32 | 2502 | 119.3 | 0.746 | 53.2 | 90.5 | 47.8 | 38.0 | 36.6 |

| ASL | 3 | 431 | 2321 | 88.6 | 0.778 | 38.1 | 58.3 | 37.1 | 30.4 | 26.5 |

| ASL | 4 | 542 | 2350 | 93.5 | 0.752 | 41.6 | 64.7 | 39.5 | 33.1 | 28.9 |

| ASL | 5 | 563 | 2372 | 90.5 | 0.741 | 42.3 | 62.6 | 41.0 | 35.8 | 29.6 |

| ASL | 6 | 472 | 2376 | 94.5 | 0.626 | 50.7 | 84.1 | 46.4 | 40.7 | 31.9 |

| ASL | 7 | 520 | 2400 | 105.0 | 0.706 | 51.4 | 81.7 | 48.8 | 41.2 | 34.1 |

| ASL | 8 | 441 | 2404 | 99.6 | 0.637 | 54.9 | 86.5 | 53.0 | 43.5 | 36.7 |

| ASL | HS | 578 | 2440 | 106.4 | 0.603 | 60.8 | 94.7 | 57.9 | 51.0 | 39.5 |

| Type | Grade | N | Mean | SD | Rho | Avg.SEM | SEM.Q1 | SEM.Q2 | SEM.Q3 | SEM.Q4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Braille | 3 | 6 | 2398 | 98.3 | 0.922 | 27.2 | 31.5 | 28.0 | 23.0 | 23.0 |

| Braille | 4 | 13 | 2474 | 103.0 | 0.931 | 26.3 | 34.3 | 23.0 | 23.3 | 23.3 |

| Braille | 5 | 15 | 2439 | 136.8 | 0.894 | 38.7 | 61.2 | 39.7 | 27.2 | 25.3 |

| Braille | 6 | 18 | 2413 | 138.3 | 0.750 | 56.5 | 111.4 | 46.2 | 37.0 | 26.8 |

| Braille | 7 | 36 | 2464 | 110.5 | 0.823 | 43.6 | 65.7 | 41.9 | 38.9 | 28.8 |

| Braille | 8 | 21 | 2435 | 90.7 | 0.704 | 48.1 | 64.0 | 49.8 | 45.6 | 36.8 |

| Braille | HS | 16 | 2441 | 103.7 | 0.478 | 66.9 | 117.0 | 62.8 | 47.5 | 41.7 |

| Spanish | 3 | 8,574 | 2366 | 85.2 | 0.847 | 30.4 | 45.3 | 28.7 | 24.6 | 22.9 |

| Spanish | 4 | 7,707 | 2400 | 87.1 | 0.837 | 32.1 | 47.9 | 30.5 | 26.1 | 23.9 |

| Spanish | 5 | 6,908 | 2416 | 91.5 | 0.793 | 38.5 | 57.0 | 38.5 | 32.6 | 26.1 |

| Spanish | 6 | 4,870 | 2417 | 103.1 | 0.715 | 48.2 | 81.2 | 46.5 | 36.1 | 29.3 |

| Spanish | 7 | 4,521 | 2408 | 98.5 | 0.632 | 53.9 | 86.6 | 52.4 | 42.8 | 33.9 |

| Spanish | 8 | 3,979 | 2422 | 102.3 | 0.626 | 57.4 | 88.2 | 55.2 | 47.9 | 38.6 |

| Spanish | HS | 3,216 | 2425 | 90.0 | 0.276 | 70.2 | 111.0 | 69.9 | 56.2 | 44.3 |

| ASL | 3 | 212 | 2325 | 85.1 | 0.791 | 35.3 | 55.7 | 34.4 | 27.4 | 23.3 |

| ASL | 4 | 266 | 2355 | 91.8 | 0.738 | 40.1 | 69.9 | 37.3 | 29.0 | 24.3 |

| ASL | 5 | 277 | 2375 | 88.3 | 0.683 | 44.5 | 69.6 | 43.3 | 37.2 | 28.2 |

| ASL | 6 | 238 | 2366 | 93.1 | 0.446 | 60.0 | 106.0 | 55.5 | 45.6 | 33.0 |

| ASL | 7 | 260 | 2393 | 105.0 | 0.610 | 58.2 | 99.4 | 54.0 | 44.9 | 34.9 |

| ASL | 8 | 221 | 2391 | 102.8 | 0.541 | 63.9 | 101.4 | 62.9 | 49.6 | 42.2 |

| ASL | HS | 295 | 2429 | 103.3 | 0.430 | 71.0 | 115.3 | 71.3 | 56.7 | 42.2 |

| TransGloss | 3 | 1,526 | 2365 | 83.8 | 0.805 | 31.3 | 51.1 | 27.9 | 23.7 | 22.7 |

| TransGloss | 4 | 1,601 | 2407 | 83.7 | 0.829 | 31.9 | 46.5 | 30.6 | 26.2 | 24.6 |

| TransGloss | 5 | 1,573 | 2424 | 92.6 | 0.802 | 37.5 | 56.5 | 36.8 | 30.8 | 25.3 |

| TransGloss | 6 | 1,448 | 2433 | 102.7 | 0.730 | 46.6 | 78.1 | 43.8 | 35.1 | 29.6 |

| TransGloss | 7 | 1,620 | 2452 | 107.9 | 0.742 | 48.5 | 78.2 | 47.7 | 38.3 | 30.3 |

| TransGloss | 8 | 1,629 | 2474 | 117.5 | 0.720 | 55.2 | 88.5 | 54.2 | 44.1 | 34.3 |

| TransGloss | HS | 645 | 2491 | 122.8 | 0.640 | 64.7 | 111.2 | 63.1 | 48.6 | 36.4 |

3.9 Differential Item Functioning (DIF)

DIF analyses are used to identify items for which groups of students that are matched on overall achievement, but differ demographically (e.g., males, females), have different probabilities of success on a test item. Information about DIF and the procedures for reviewing items flagged for DIF is a component of validity evidence associated with the internal properties of the test.

3.9.1 Method of Assessing DIF

DIF analyses are performed on items using data gathered in the field test stage. In a DIF analysis, the performance on an item by two groups that are similar in achievement, but differ demographically, is compared. In general, the two groups are called the focal and reference groups. The focal group is usually a minority group (e.g., Hispanics), while the reference group is usually a contrasting majority group (e.g., Caucasian) or all students that are not part of the focal group demographic. The focal and reference groups in Smarter Balanced DIF analyses are identified in Table 3.6.

| Group Type | Focal Group | Reference Group |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | Male |

| Ethnicity | African American | White |

| Ethnicity | Asian/Pacific Islander | White |

| Ethnicity | Native American/Alaska Native | White |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | White |

| Special Populations | English Learner (EL) | English Proficient |

| Special Populations | Individualized Education Program (IEP) | Non-IEP |

| Special Populations | Lower Social Economic Status (Econ) | Non-Econ |

A DIF analysis asks, “Do focal group students have the same probability of success on each test item as reference group students of the same overall ability (as indicated by their performance on the full test)?” If the answer is “no,” according to the criteria described below, the item is said to exhibit DIF.

Different DIF analysis procedures and flagging criteria are used depending on the number of points the item is worth. For one-point items (also called dichotomously scored items and scored 0/1), the Mantel-Haenszel statistic (Mantel & Haenszel, 1959) is used. For items worth more than one point (also called partial-credit or polytomously scored items), the Mantel chi-square statistic (Mantel, 1963) and the standardized mean difference (SMD) procedure (Dorans & Kulick, 1983, 1986) are used.

The Mantel-Haenszel statistic is computed as described by Holland & Thayer (1988). The common odds ratio is computed first:

\[\begin{equation} \alpha_{MH}=\frac{(\sum_m\frac{R_rW_f}{N_m})}{(\sum_m\frac{R_fW_r}{N_m})}, \tag{3.1} \end{equation}\]

where

\(R_r\) = number in reference group at ability level m answering the item right;

\(W_f\) = number in focal group at ability level m answering the item wrong;

\(R_f\) = number in focal group at ability level m answering the item right;

\(W_r\) = number in reference group at ability level m answering the item wrong; and

\(N_m\) = total group at ability level m.

This value is then used to compute MH D-DIF, which is a normalized transformation of item difficulty (p-value) with a mean of 13 and a standard deviation of 4:

\[\begin{equation} -2.35ln[\alpha_{MH}]. \tag{3.2} \end{equation}\]

The standard error (SE) used to test MH D-DIF for significance is equal to

\[\begin{equation} 2.35\sqrt{(var[ln(\hat{\theta}_{MH})])}, \tag{3.3} \end{equation}\]

where the variance of the MH common odds ratio, \(var[ln\hat{\theta}_{MH})],\) is given for example in Appendix 1 of Michaelides (2008). For significance testing, the ratio of MH D-DIF and this SE is tested as a deviate of the normal distribution (\(\alpha = .05\)).

The statistical significance of MH D-DIF could alternatively be obtained by computing the Mantel chi-square statistic:

\[\begin{equation} X^2_{MH} = \frac{(|\sum_m R_r-\sum_m E(R_r)|-\frac{1}{2})^2}{\sum_m Var(R_r)}, \tag{3.4} \end{equation}\]

where

\[\begin{equation} E(R_r) = \frac{N_r R_N}{N_m,Var(R_r)} = \frac{N_r N_f R_N W_N}{N_m^2 (N_m-1)}, \tag{3.5} \end{equation}\]

\(N_r\) and \(N_f\) are the numbers of examinees in the reference and focal groups at ability level m, respectively, and \(R_N\) and \(W_N\) are the number of examinees who answered the item correctly and incorrectly at ability level m, respectively. Smarter Balanced uses the standard error to test the significance of MH D-DIF.

The Mantel chi-square (Mantel, 1963) is an extension of the MH statistic, which, when applied to the DIF context, presumes the item response categories are ordered and compares means between reference and focal groups. The Mantel statistic is given by:

\[\begin{equation} X^2_{Mantel} = \frac{(\sum_{m=0}^T F_m - \sum_{m=0}^T E(F_m))^2}{\sum_{m=0}^T \sigma_{F_m}^2} \tag{3.6} \end{equation}\]

where \(F_m\) is the sum of item scores for the focal group at the \(m^{th}\) ability level, E() is the expected value (mean), and \(\sigma^2\) is the variance. (Michaelides, 2008, p. 5) provides additional detail pertaining to the computation of the mean and variance.

The standardized mean difference used for partial-credit items is defined as:

\[\begin{equation} SMD = \sum p_{Fk} m_{Fk} - \sum p_{Fk} m_{Rk}, \tag{3.7} \end{equation}\]

where \(p_{Fk}\) is the proportion of the focal group members who are at the \(k^{th}\) level of the matching variable,\(m_{Fk}\) is the mean item score for the focal group at the \(k^{th}\) level, and \(m_{Rk}\) is the mean item score for the reference group at the \(k^{th}\) level. A negative value of the standardized mean difference shows that the item is more difficult for the focal group, whereas a positive value indicates that it is more difficult for the reference group.

To get the effect size, the SMD is divided by the total item group (reference and focal groups pooled) standard deviation:

\[\begin{equation} SD = \sqrt{\frac{(n_F-1)\sigma_{y_F}^2+(n_R-1)\sigma_{y_R}^2}{n_F + n_R - 2}}, \tag{3.8} \end{equation}\]

where \(n_F\) and \(n_R\) are the counts of focal and reference group members who answered the item, and \(\sigma_{y_F}^2\) and \(\sigma_{y_R}^2\) are the variances of the item responses for the focal and reference groups, respectively.

Items are classified into three categories of DIF: “A,” “B,” or “C” according to the criteria shown in Table 3.7 (for dichotomously scored items) and Table 3.8 (for partial-credit items). Category A items contain negligible DIF. In subsequent tables, category A levels of DIF are not flagged as they are too small to have perceptible interpretation. Category B items exhibit moderate DIF, and category C items have significant values of DIF. Positive values favor the focal group, and negative values favor the reference group. Positive and negative values are reported for B and C levels of DIF. Negative and positive DIF at the B level are denoted, respectively, B- and B+. Likewise for C-level DIF.

| DIF Category | Definition |

|---|---|

| A (negligible) | |MH D-DIF| < 1 |

| B (slight to moderate) | |MH D-DIF| \(\ge\) 1 and |MH D-DIF| < 1.5 |

| B (slight to moderate) | Positive values are classified as ‘B+’ and negative values as ‘B-’ |

| C (moderate to large) | |MH D-DIF| \(\ge\) 1.5 |

| C (moderate to large) | Positive values are classified as ‘C+’ and negative values as ‘C-’ |

| DIF Category | Definition |

|---|---|

| A (negligible) | Mantel chi-square p-value > 0.05 or |SMD/SD| \(\le\) 0.17 |

| B (slight to moderate) | Mantel chi-square p-value < 0.05 and 0.17 < |SMD/SD| \(\le\) 0.25 |

| C (moderate to large) | Mantel chi-square p-value < 0.05 and |SMD/SD| > 0.25 |

Items flagged for C-level DIF are subsequently reviewed by content experts and bias/sensitivity committees to determine the source and meaning of performance differences. An item flagged for C-level DIF may be measuring something different from the intended construct. However, it is important to recognize that DIF-flagged items might be related to actual differences in relevant knowledge and skills or may have been flagged due to chance variation in the DIF statistic (known as statistical type I error). Final decisions about the resolution of item DIF are made by the multi-disciplinary panel of content experts.

3.9.2 Item DIF in the 2021-22 Summative Assessment Pool

Table 3.9 and Table 3.10 show DIF analysis results for items in the 2021-22 ELA/literacy and mathematics summative item pools. The numbers of items with moderate or significant levels of DIF (B or C DIF) in the summative pools were relatively small. Items classified as N/A (not assessed) were items for which sample size requirements were not met. Most of these cases occurred for the Native American/Alaskan Native focal group. These students comprised only about 1% of the total test-taking population.

| Grade | DIF Category | Female Male | Asian White | Black White | Hispanic White | Native American White | IEP NonIEP | EL NonEL | Econ NonEcon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | A | 997 | 934 | 908 | 963 | 332 | 974 | 942 | 992 |

| 3 | B- | 10 | 42 | 80 | 46 | 13 | 37 | 65 | 16 |

| 3 | B+ | 9 | 54 | 14 | 6 | 7 | 10 | 5 | 0 |

| 3 | C- | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 2 |

| 3 | C+ | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | NA | 482 | 464 | 494 | 479 | 1145 | 476 | 480 | 488 |

| 4 | A | 1049 | 987 | 981 | 1016 | 328 | 1014 | 963 | 1051 |

| 4 | B- | 20 | 54 | 80 | 67 | 14 | 54 | 105 | 29 |

| 4 | B+ | 16 | 54 | 12 | 3 | 5 | 13 | 6 | 1 |

| 4 | C- | 2 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 5 | 15 | 1 |

| 4 | C+ | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | NA | 447 | 432 | 459 | 443 | 1188 | 449 | 446 | 453 |

| 5 | A | 1181 | 1097 | 1087 | 1151 | 358 | 1143 | 1063 | 1191 |

| 5 | B- | 31 | 72 | 104 | 73 | 16 | 65 | 143 | 29 |

| 5 | B+ | 23 | 65 | 22 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 7 | 2 |

| 5 | C- | 7 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 8 | 17 | 0 |

| 5 | C+ | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | NA | 371 | 375 | 398 | 378 | 1236 | 391 | 385 | 393 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6 | A | 951 | 939 | 938 | 999 | 313 | 984 | 893 | 1033 |

| 6 | B- | 33 | 60 | 84 | 53 | 10 | 54 | 149 | 18 |

| 6 | B+ | 59 | 52 | 16 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| 6 | C- | 8 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 13 | 15 | 0 |

| 6 | C+ | 22 | 23 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | NA | 418 | 410 | 443 | 426 | 1155 | 435 | 430 | 437 |

| 7 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 7 | A | 1003 | 993 | 1019 | 1068 | 293 | 1060 | 959 | 1099 |

| 7 | B- | 47 | 55 | 67 | 53 | 9 | 56 | 142 | 22 |

| 7 | B+ | 83 | 70 | 19 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 1 |

| 7 | C- | 6 | 4 | 6 | 10 | 0 | 5 | 18 | 2 |

| 7 | C+ | 22 | 26 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | NA | 373 | 385 | 417 | 399 | 1223 | 405 | 410 | 410 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 8 | A | 931 | 926 | 956 | 1008 | 297 | 970 | 876 | 1035 |

| 8 | B- | 49 | 62 | 63 | 45 | 7 | 75 | 156 | 22 |

| 8 | B+ | 84 | 68 | 26 | 14 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 0 |

| 8 | C- | 9 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 15 | 18 | 3 |

| 8 | C+ | 31 | 21 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | NA | 385 | 406 | 436 | 412 | 1178 | 424 | 429 | 429 |

| 11 | 1 | 2 | 47 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 11 | A | 1493 | 1448 | 1529 | 1519 | 1032 | 1580 | 1424 | 1605 |

| 11 | B- | 136 | 121 | 67 | 168 | 10 | 87 | 195 | 89 |

| 11 | B+ | 68 | 103 | 41 | 31 | 16 | 28 | 29 | 13 |

| 11 | C- | 17 | 8 | 6 | 11 | 4 | 12 | 36 | 3 |

| 11 | C+ | 30 | 23 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| 11 | NA | 1231 | 1271 | 1281 | 1244 | 1909 | 1265 | 1289 | 1265 |

| Grade | DIF Category | Female Male | Asian White | Black White | Hispanic White | Native American White | IEP NonIEP | EL NonEL | Econ NonEcon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | A | 862 | 793 | 800 | 837 | 374 | 855 | 843 | 877 |

| 3 | B- | 31 | 39 | 77 | 78 | 6 | 53 | 66 | 35 |

| 3 | B+ | 25 | 123 | 66 | 40 | 7 | 19 | 27 | 3 |

| 3 | C- | 5 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| 3 | C+ | 1 | 23 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 0 |

| 3 | NA | 770 | 713 | 738 | 732 | 1296 | 763 | 749 | 779 |

| 4 | A | 1036 | 928 | 984 | 1044 | 436 | 1005 | 993 | 1061 |

| 4 | B- | 56 | 51 | 84 | 70 | 12 | 100 | 112 | 53 |

| 4 | B+ | 33 | 167 | 49 | 26 | 15 | 14 | 28 | 4 |

| 4 | C- | 10 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 16 | 1 |

| 4 | C+ | 1 | 22 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| 4 | NA | 788 | 751 | 794 | 776 | 1458 | 800 | 772 | 805 |

| 5 | A | 977 | 851 | 903 | 978 | 435 | 927 | 941 | 1012 |

| 5 | B- | 62 | 42 | 86 | 65 | 7 | 109 | 100 | 42 |

| 5 | B+ | 21 | 181 | 56 | 15 | 15 | 24 | 20 | 3 |

| 5 | C- | 11 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 12 | 11 | 0 |

| 5 | C+ | 0 | 25 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | NA | 766 | 734 | 783 | 775 | 1375 | 764 | 765 | 780 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6 | A | 948 | 864 | 852 | 934 | 343 | 893 | 886 | 957 |

| 6 | B- | 44 | 40 | 46 | 67 | 4 | 79 | 88 | 48 |

| 6 | B+ | 33 | 120 | 31 | 15 | 6 | 21 | 20 | 6 |

| 6 | C- | 2 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 11 | 11 | 3 |

| 6 | C+ | 1 | 33 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 6 | NA | 676 | 642 | 757 | 681 | 1344 | 700 | 697 | 690 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 69 | 0 | 443 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 7 | A | 968 | 895 | 764 | 937 | 295 | 947 | 900 | 966 |

| 7 | B- | 70 | 30 | 26 | 102 | 0 | 76 | 101 | 87 |

| 7 | B+ | 30 | 149 | 19 | 25 | 6 | 24 | 19 | 6 |

| 7 | C- | 4 | 5 | 14 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 10 | 4 |

| 7 | C+ | 0 | 33 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 0 |

| 7 | NA | 643 | 603 | 820 | 643 | 968 | 659 | 679 | 652 |

| 8 | 0 | 2 | 37 | 0 | 432 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 8 | A | 909 | 778 | 723 | 890 | 282 | 839 | 799 | 910 |

| 8 | B- | 39 | 36 | 47 | 57 | 3 | 96 | 90 | 47 |

| 8 | B+ | 17 | 106 | 22 | 24 | 3 | 16 | 13 | 4 |

| 8 | C- | 2 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 10 | 22 | 1 |

| 8 | C+ | 0 | 18 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 0 |

| 8 | NA | 588 | 610 | 718 | 580 | 831 | 588 | 629 | 593 |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 67 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 11 | A | 852 | 785 | 646 | 842 | 317 | 760 | 710 | 861 |

| 11 | B- | 61 | 28 | 29 | 85 | 2 | 72 | 67 | 62 |

| 11 | B+ | 57 | 124 | 43 | 43 | 6 | 26 | 29 | 21 |

| 11 | C- | 14 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 15 | 22 | 3 |

| 11 | C+ | 8 | 41 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 7 | 4 |

| 11 | NA | 1983 | 1995 | 2179 | 1995 | 2640 | 2099 | 2140 | 2024 |

3.10 Test Fairness and Implications for Ongoing Research

The evidence presented in this chapter underscores the Smarter Balanced Consortium’s commitment to fair and equitable assessment for all students, regardless of their gender, cultural heritage, disability status, native language, and other characteristics. In addition to these proactive development activities designed to promote equitable assessments, other forms of evidence for test fairness are identified in the Standards (2014). They are described and referenced in the validity framework of Chapter 1.